Surviving the Ice Age in Northern Indiana

By James Holtzclaw, Interpretive Naturalist

Explore the serene Boot Lake Nature Preserve, where you can wander through the lush grasslands and the quiet woodlands. Take a moment at the observation deck, which offers views of the lake where the still water caresses the mudflats. Feel the gentle breeze as it flows through the Button Bushes and listen to the Sandhill Crane’s trumpet-like calls while they forage through the weeds and muck. As you look out, remember that you are not just looking at a breathtaking wetland; you’re gazing at a fossil shaped since the end of the Ice Age. This living fossil has stories to tell—tales of a time of a chaotic environment, vanishing great beasts, and the endurance of the first Americans. These epic narratives are entwined into a larger canvas of history, offering invaluable lessons that can reverberate for generations if only we can take the time to listen to them at Boot Lake Nature Preserve.

Boot Lake was a product of climate change. It formed at the end of the Ice Age when glaciers receded northward. During this time of glacial recoil, a massive chunk of ice broke off, creating a depression in the earth. Later, this hollow filled with meltwater from the ice, along with rain and snowmelt, creating a kettle lake. In a sense, climate change gave us a place to walk, relax, and connect with nature. But the Paleo-Americans who experienced this climate change, who roamed this area, didn’t stop to look at a giant block of ice melting and hoped that this area would turn into a park for generations to come. The Paleo-Americans, like the rest of their tribe, roamed this area to hunt and gather food in this strange world.

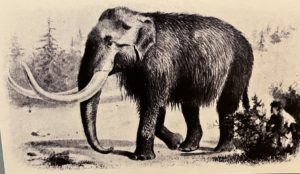

During the late Ice Age, Paleo-Americans navigated a chaotic, alien environment that was much different than today’s. They roamed a landscape consisting of wetlands and grasslands, with nearby forests comprising spruce, balsam firs, tamaracks, birches, and aspen trees. They coexisted with enormous creatures on the brink of extinction, including the mammoths, the mastodons, the saber-toothed tigers, and the short-faced bears. If they lived along the glacier’s edges, their view was dominated by a half mile to a-mile high wall of ice. An imposing barrier that would strike fear in anybody who tried to explore it. Paleo hunters who ventured into the tundra-like environment that stretched from the glacier faced harsh conditions, including katabatic winds—frigid gales that swept off the glacier’s surface, capable of cutting down both man and beast. In the summer, these hunters trudged through mud, drenched by constant glacier-effect rain, and in the winter, they would be frigid in the glacier-effect snow. Yet, these hardy people survived in this tumultuous world by working together in bands of close-knit families.

The Paleo people were America’s first hunters and gatherers. They traveled in bands of twenty to fifty people and were known to hunt mammoths and mastodons due to their spearpoints found at megafauna kill sites. Yet, archaeological and Inuit ethnographic evidence proved that they were not just mammoth hunters but also generalist foragers who used local resources for survival. At a mammoth butchered site in Wyoming, archaeologists discovered sewing needles crafted not from megafauna bones but bones from red foxes, lynx, and rabbits. Inuit ethnographies suggested that Paleo-Americans may have consumed licorice roots, wood sorrel, and blue berries. Therefore, their diet did not consist of just megafauna meat but of smaller game and, when available, plant material. Their generalist approach to hunting and gathering proved that these people were resilient, especially in how they procured their meat.

Paleo bands hunted big game and smaller animals to be able to provide meat for their people. They most likely used a trapping technique to hunt foxes, rabbits, and squirrels. But they had to use a different approach to take down mammoths and other megafauna from a safe distance; they had to use a tool called an atlatl. The atlatl was a stick with a hook on the end. Hunters would use an atlatl to launch a long dart at their prey. The dart’s tip was made from a sharp stone point designed to pierce an animal’s hide. As the Paleo bands adapted their hunting strategies for both small game and formidable megafauna, they were unaware that these specialized methods would soon be put to the test by dramatic environmental changes and the eventual loss of their primary food sources, the megafauna. So, how did these people react to this change? The famous naturalist Aldo Leopold had the best answer to this question. He wrote, “The Cro-Magnon who slew the last mammoth thought only of steaks,” and like the Cro-Magnon who lived in Europe, the Paleo-Americans also thought of their empty stomachs when they butchered the last mammoth in the Americas, and with that attitude, the Paleo Americans did not debate climate change, habitat change, or species extinction but focused on adapting to survive in their new world.

In central Indiana, this new environment consisted of parklands with a mix of coniferous and deciduous forests, wetlands, and vanishing grasslands, but in Northern Indiana, a boreal-dominated parkland still existed. The Paleo-Americans in both areas had different hunting and gathering strategies to help them survive. Those who lived in Central Indiana focused on hunting deer and other small game and harvesting nature’s produce: nuts, berries, and roots. In Northern Indiana, the Paleo-Americans focused on hunting migratory big animals like the caribou, which took strategic planning.

Caribou hunters’ ethnographies and archaeological evidence were important in giving us insight into how the late Paleo-Americans preyed on these great beasts. In the central Canadian Arctic, the Inuit hunters pursued the caribou during fall migration when these animals were healthy and plumped. This allowed them to prepare hides and make tools for the upcoming winter and to cache caribou meat when there was a food shortage. These arctic hunters would herd the caribou through boulder lines, limiting these creatures’ space. The hunters would shoot the caribou while hiding behind a blind. In recent years, archaeologists discovered these types of hunting structures under Lake Huron that date to the Late Paleo Period. Their discovery proved that this hunting strategy had been passed down nearly ten thousand years ago. Still, it was more than tradition but an adaptation how Paleo-Americans survived the late Ice Age when the megafauna went extinct.

The Paleo-Americans’ adaptation to their changing world was a testament to humanity’s desire to survive. We always envisioned them in an epic scene where they used their atlatls to throw darts at a mammoth. These people were more than that. They were like us. They had traditions, religions, families, and a desire to live. If they visited with us today, what would they say or teach us about their experience at the end of the Ice Age? Many might say that they would tell us that man conquered nature, or that man rose above nature. To me, they would say something like this: our environment is fluid; it never stays the same. They would be right since they experienced this change. We could see this lesson at Boot Lake Nature Preserve.

*image from Elkhart County Historical Museum